The whole village has chicha in their veins. Lying in bed, I can hear a constant wail of noise that rises and falls. It is like a sea, punctuated by the hoots and cheers of women.

Meals are sparse during the ceremony. Breakfast is boiled yuca with a single sunny side up. It’s also because we have run out of vegetables.

Women are sat together in the temporary house. Only women are allowed in, but the men loiter outside, looking in. The chicha music comes and goes.

Drunk language is English. It’s great how everyone practices English when they are drunk.

After breakfast the women all sit in and around the temporary house. The immediate family and relatives of the girl sit inside. All women. They will begin the ceremony of cutting her hair at 10am. Buckets of dark looking chicha are drawn up and passed around.

I follow the men into the chicha house. It’s barely nine in the morning. There are two singers in the hammock; their singing is more of a half shout, atonal, continuous and punctuated by the rhythmic maracas that they shake in their hands. The smoke palls all around, it heats up the house. We are brought a small tortuma of chicha. This time, I take small sips and chase it with water. Then they bring Luis a large tortuma. He manages to down half of it and passes it to me. The chicha has fermented even more over the past two days. It is dark, almost fizzy and very, very strong. But because we are not expected to drink it all at once, it is a lot more palatable.

All the men have to vamos from the chicha house and from the house of the women. We walk past the basketball court and pull up plastic chairs. Someone hands all of us a beer. Luis, who is gluten intolerant, goes for his usual rum in a mineral water bottle. Ramiro Martinez, drunk as a skunk, draws ‘thank you’ on the sand.

Lucho mara leche means Lucho (Luis) is bad milk. It’s a drunk joke from Ramiro Martinez. I suppose it means the same as a rotten egg.

The tourists are still here. Apparently, their boat driver is too drunk so they will only leave tomorrow. The two French boys are engineering students and they are taking a gap year to travel and work on various ecological engineering projects. Various organisations and their university fund it. This is the holiday portion of their trips. A pretty good gig. While students in Singapore rarely take gap years and sometimes overload their semesters. And holidays are spent on multiple internships, maxing out their CVs. What a dank life.

Doing laundry while slightly high is like an act of cleansing. Rinse, soap, wash, wring. Repeat.

Luis is in the other house, so we work on a spoken word piece and another lyric that I wrote a few days ago. We are both not fully there but the art takes over, and we are able to concentrate and figure out something decent. The girls have gone for a beer and are still at the women’s house. Just as we are starting to record a demo of our song, I’m incredibly distracted by the sight of a naked man walking up from the river after having taken a shower, looking like a pudgy yet muscular vision of John the Baptist.

At the women’s house, women put oil in their hair and powder on their faces. According to Maria, she felt like a baby for a while. Everyone is drinking, of course. The girl’s hair is cut in rows, very slowly, close to the scalp.

Verónica comes back to Nacho’s house around lunch to apply sunblock. She tells me that the ceremony is still ongoing. I walk over for a peek. It’s just a horde of drunken women in there. The girl is still in the hammock.

Igua doesn’t drink. He’s working on a watercolour painting and seems to be disinterested in the chicha. He also wears a cross around his neck. I wonder if he’s the designated adult for the house, or whether he objects on religious grounds.

There is some concern about having allowed the tourists’ to be part of the chicha, because they were not briefed about protocol beforehand. This resulted in some uncomfortable moments, and apparently one of the French dudes grabbed Nacho’s ass at some point 🤪

Nague made lunch today, because Aida was out drinking.

Charlotte, Verónica and Maria return and between the three of them I try to piece together what happened during the ceremony.

There were five women sitting on towels on the floor and one in the middle was holding the girl. It’s the aunt of the girl, because the mother doesn’t drink alcohol and so she isn’t allowed inside. Something powerful here about the relationship between alcohol and permission. A woman on their left was chanting and across the women was three low stools with women who were smoking tobacco and cacao in containers as incense. Other women smoked tobacco in the faces of the other women who lined the house.

Behind the women of the girl was the woman who would cut the hair. Her name is Iét. At one point the chicha finished so everyone collected money to buy beer. They poured all the beer into the chicha bucket and passed it around like it was chicha.

The women cut one lock of hair at a time in lines. They started in the centre and moved outwards. Men came in and they painted them with red pigment and powder. Then everyone ate dried fish and plantains. The men left.

When the girl was bald they undressed and washed her. They carried her and washed her near the house. They put some leaves and dressed her in a new, white mola. Whenever they carried her they were dancing. The girl was always wearing a scarf on her head. They put a leaf on her lap and a veil on her whole body.

Iét started singing again.

At some point the men came in again and held the hand of the singing woman. The woman sang to the men and then they left.

At the end they pulled out a hammock and put the girl in the hammock. The formal element was over and everyone relaxed and took photos and told jokes.

After lunch, the men are still singing in the chicha house and there’s still a group of men smoking around them. Chicha is still being passed around. At this point, people are staggering about or starting to walk sideways like crabs. A wall of a nearby house, made of sticks, has collapsed. But all in all, it’s not raucous or manic.

Suddenly tired, I take a nap while listening to Mumford and Sons, ‘Delta’; Then I read bits of Anis Mojgani’s book, ‘In The Pocket of Small Gods’; terribly devastating but also deep and true.

Everyone writes or draws something for Bernie on small colourful cards that Veronica has brought with her. It’s her birthday today! I write her a poem.

Wish

(for Berenike, on her birthday)

Each stroke of your brush

is a journey towards another story.

Everything finds light

under the sunshine of your touch.

Unfold flowers from lost things,

give them new names.

Hold yourself

up to the sun,

that you may sew new colours

across tall fields of grass.

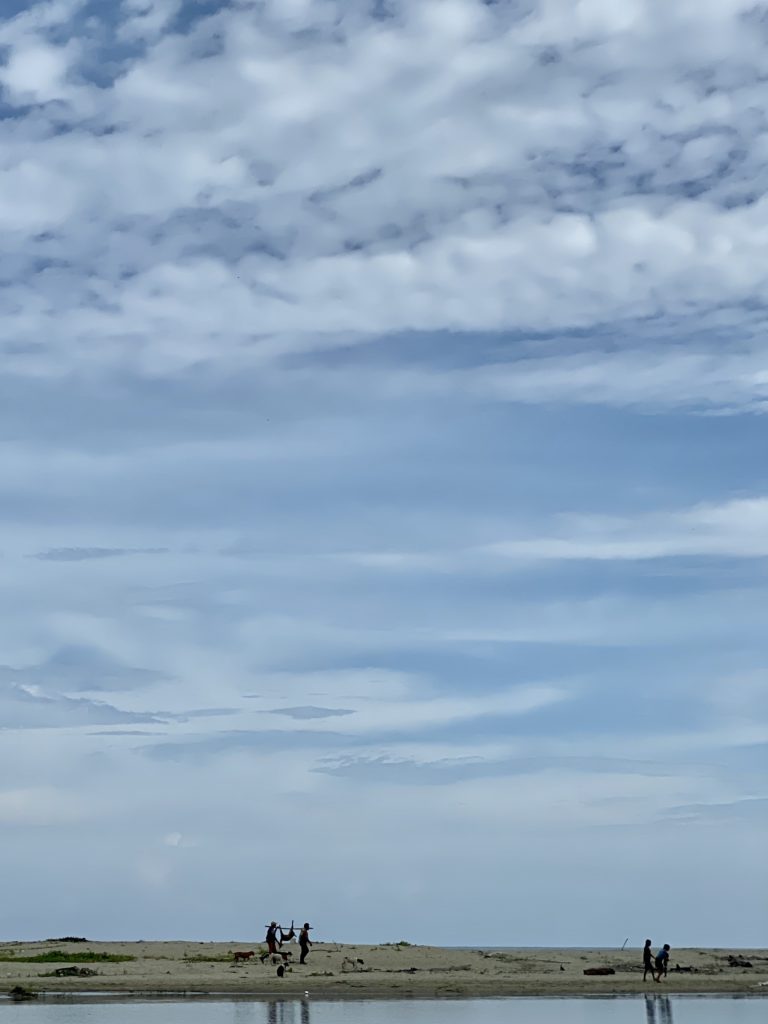

A large group of men and women return from the beach looking very drunk. One of them is holding an empty chicha bucket. They certainly weren’t building sandcastles. Luis says that they went swimming naked in the sea.

Back at the house, Caroline, Maria and I start talking about Sellavision and memories of home shopping. It’s always things that we never needed but the people with pearly-white smiles and $39.90 deals always won us over. Plus if we ordered right now, they would throw an extra thingamajig that alone was worth $39.90. Just think of the value!

From this, we sidetrack to contests at the back of cereal boxes. Caroline has a great story of when her mother was a kid and she drew a pirate and sent it in and some time later two men showed up at her door, wanting to offer her more prizes because, “You’ve got talent, kid” I ask if Caroline’s mother eventually became an artist. She was a homemaker and after twenty years of raising kids, returned to work in a nephrology unit at a hospital. When she started she couldn’t figure out how to check her email!

And then, drama! Someone broke into the other house and when Bernie, Charlotte and Veronica returned from a walk, they heard a loud clatter but weren’t quick enough to see what it was. Apparently, a young boy, fourteen, had climbed in through the bathroom window and rifled through Bernie’s things, stealing money and a power bank. She was very affected because earlier this year, she had another incident in London where thieves snuck into her apartment and made off with her suitcase. And it happened when she had come home and caught them in the act. But there was no way to retrieve what she lost then, and that fear feeds into what has just happened. Fortunately, some ladies saw the boy climb out the window and told Aida, who went on the warpath and set a neighbourhood watch out for him. He stupidly tried to buy juice at a store and was caught red-handed. It’s a small community, and there really is nowhere to run. The boy is a recalcitrant. This will be his third strike. Apparently he had already been hauled up to the council before for being an unrepentant smoker. We manage to retrieve some of the money, but Luz says the family will return everything, although a power bank is still missing. But it’s more about the emotional toll on Bernie as well as the shock of something like this happening to us.

The Internet lady has more power than the sahila in this village. Another quip from Caroline.

The chicha is still going on, but people have already started going back to other communities. In the chicha house the men continue to surround the cantule, who seems to be singing all the way to the merry end.

We sit outside after dinner. The stars keep changing colour from red to blue to green to white. A star has just turned off. Maybe it was a satellite that expired. Maybe the star’s light finally depleted, millions of years after its death. Strange to think about legacies and the kinds of light they emanate.

We talk about spending time in airports. Luis moves from that to the time when he lived through an earthquake. He was a kid and traveling with his family. They were meant to fly that day from the north of Chile, but the flight was overbooked. His parents were incensed and argued for hours but they weren’t put on the flight. They refused the offer of a hotel to spend the night so the family went back to a house they had in the city. At night the entire house started shaking. Everybody ran out. The aftershocks lasted through the night. A lot of buildings collapsed (maybe even the hotel they were supposed to stay at!) and the airport was closed for two weeks. If they had made that flight, they would have escaped it all.