The large papaya has been cut down from the tree. It is twice the size of my head! It’ll take another four days to ripen. Papaya in Guna means a woman’s privates. It is not so straightforward buying fruit here!

Over breakfast, Nacho tells us a bit more about the turtles. Up to five different species of turtles come to Armila to lay their eggs from Feb to June every year. Armila is a critical nesting point for the turtles, which will stay for up to two months until the eggs hatch. Some nights as many as 50 turtles, including the sacred leatherbacks, will mount the shore. It is forbidden to eat or make anything from the turtles here in Armila, though other Guna communities elsewhere do consume the smaller turtles, like the Hawksbill and Green Turtles. The Leatherback is considered sacred across all the communities.

The conversation moves to history and Nacho pulls out a Spanish book that lists some of the key figures of the Guna from the 19th and 20th centuries. He explains the origin of the flag, which was devised by a woman (of course!) and used as a standard in the 1925 revolution.

I mistake tortuma (calabash) with tortuga, turtles. It is the tortuma, a hollowed out gourd,that is used in one of the ritual ceremonies of the Guna.

Luis mentions that the turtles eat hedgehogs. Hilarity. It emerges that the Spanish word for Hedgehog and sea urchin are the same. Erizo. Perhaps sea urchins once were hedgehogs. Lost under the sea, they slowly forgot the taste of wood and soil.

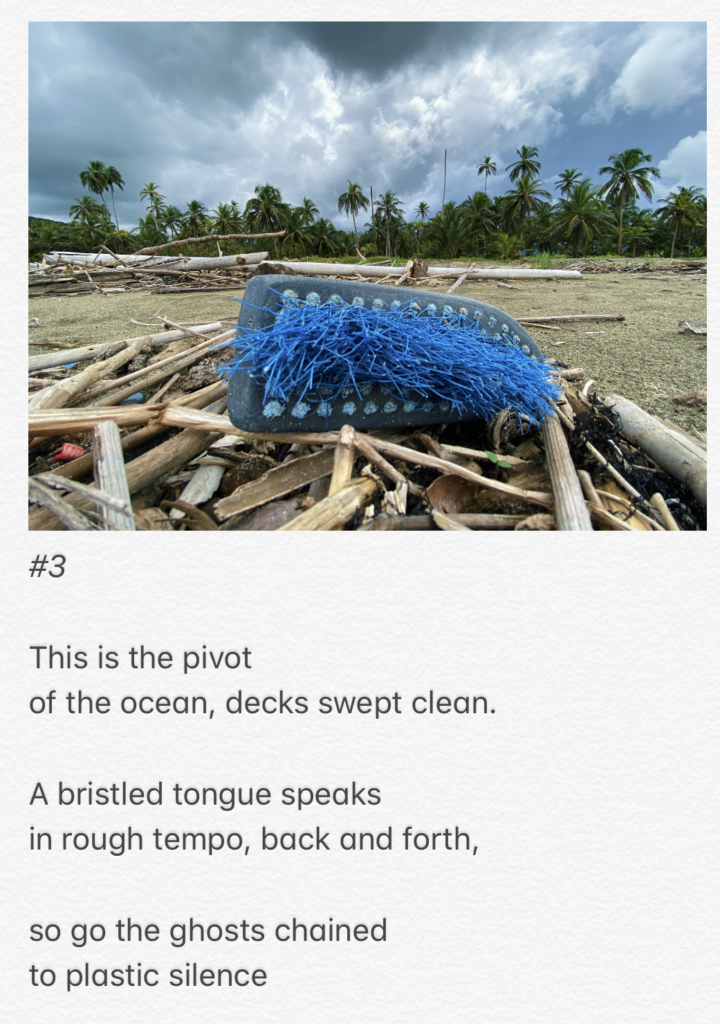

Trash is normalized for the young kids. They have not known a time when the beach was clean, pristine. When the world wasn’t as heavy with all the weight of this undying skin.

I spend an hour digging a hole in front of our house. At first, I am trying to look for stones or shells. Then I recognise that I am making the shape of a coconut, inspired perhaps by the half coconut that sits in front of the door. I place the coconut in the hole and arrange twelve stones around it. The coconut is now a clock. I take a picture and then write a poem around this idea.

After lunch, which is a tasty fish broth with plantain, rice and salad, I make my usual daily sketch + poem of plastic trash. Today it is a scrubbing brush.

This afternoon’s lecture is on the imagery behind the mola. Nacho draws all of the different symbols out and tells us the story behind how they came to be. They are everyday objects, turtles, mountains, etc.

Then Jessica, a local artisan, gives us a live demonstration of how a mola is sewn. The layers are intricate and it is a primer for the more complex patterns laid out on the other table. Everyone lunges for the different molas. It is frenzy. and I buy two. One is a mountain and the other is a pair of animals that make up the meaning of Armila in Guna, an iguana and a fish.

It’s not as if there are loads of molas on offer. The ones we see have been sewn over months and are of a pretty high standard. All of the tourists who stay at the more popular Guna areas such as San Blas will never see molas such as these.

After class, we cross the river to gather firewood for a fire. It has been a clear, hot afternoon, and the wood is dry enough. The fire is behind Nacho’s house, and becomes a welcome way to end the day. A round of MF beers seals the deal.

The fireflies are stars that have come to visit for a while.

We speak of revolutions near and far. Some happening even now, in the places we call home. Others that reverberate, not across continents but through the heart of people who are tired of being forced to consume everything. They have seen that needing more is the lie that must be devoured. But how? Meanwhile, the artist comes and goes, crossing borders and belief systems, while holding on to that small knot of knowledge to call their own; whether it be a song, a sculpture or even a melody that needs no home.