Angelica was adopted recently by Aida and Igua, her husband. She’s 11 and was the unwanted child when her mother remarried. She is from another community and has never been to school in her life. She will start next year, but it’s amazing how she has fit so naturally into the family and how they see her as one of their own, wholeheartedly. This is Aida’s second marriage and Nachito, all of three, is the product of her bond with Igua. Aida’s two kids from her first marriage are Nague and Zlatan. Families are patchwork, hard work, a constant sewing of sutures. I think of the tablecloth used at Nague’s party. It’s a beautiful blend of different molas that come together like a symphony or, for the Guna, a dance.

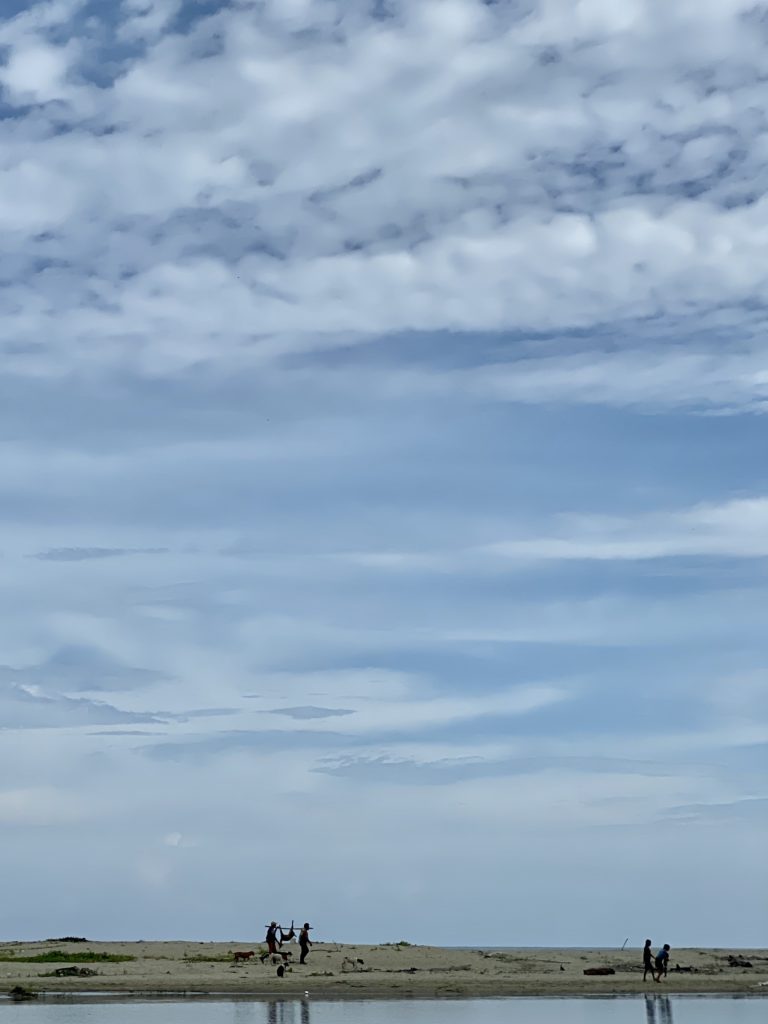

We travel for close to thirty minutes in the speedboat to reach Anachucuna, another Guna community. As we are leaving Armila, two men walk across the sandbar towards the village, carrying a deer on a stick between them.

We are staying in the house of Baudeliano Perez, the counterpart of Nacho, here in Anachucuna. He was born across the river from where the village is today. In 1972, the village moved to their present location. They were further down the coast, closer to Armila, before.

There are two stories about how Anachuchuna got its name:

A foreigner met a lady from the community in the jungle with her dog. He asked her in Spanish what the name of the community was. She didn’t understand and thought he was referring to her dog. So she said, “this is my dog”. In Guna, this sounds like Anachucuna. Another meaning is more natural, ‘Where the bay narrows to the river.’

The Guna name for the town is Assuamulo – the avocado tree.

There are 650 people living here between the two towns. The new town, twelve years old, is a ten minute walk through a large coconut plantation, which is a community crop shared by 38 families.

The villagers fish and cultivate crops, specifically coconuts. Traders from Columbia come here to barter with sheep and rice and other essentials. Students study until 9th grade (14 years) and then go elsewhere. Baudeliano says that they would like to even have a university in some part of the comarca (region, or county), where the Guna live.

The banana planters left Anachucuna in 1947. They left behind the tracks and rusted out hulls of their little engines. It was a short train line, spanning the coastline between Anachucuna and Armila. The remains of an old jetty can be seen by the water. Some of the planters, who were little more than indentured slaves, chose to remain and settled down but all of them eventually left because the locals were not keen about having outsiders.

The village is laid out very geometrically in a grid-like fashion. Ordered, with lots of work being done on various houses. The girls are staying in an extension of Baudeliano’s house. Luis and I are in a house on the other side of the village. It is a clean, well-furnished room. We each have a queen bed to ourselves!

After lunch – chickpea patties fried by Luis, hamburger buns, boiled yuca and salad – all the ingredients brought from Armila, we head to a beach ten minutes away by boat. The community is out of sight and Luz allows me to fly the drone. I make a couple of low passes over a small island in front. It’s a tiny rock with some vegetation and palm trees, surrounded by rippling, rich blue. The drone loses its line of communication as I am bringing it back but I can see it and manage to land it safely.

The rest of the afternoon is spent looking for shells in the shore and in the water, swimming to that island and trying not to graze the coral in the extremely shallow water. The hours pass comfortably. Bernie returns with a lovely large conch; pink in the middle. Maria finds the bones of a pelican’s beak, stripped clean by the tide. I have a small assortment of shells.

An almost throwaway line from Maria – ‘When we grow up we need less repetition.’ Maybe structurally, we are already set in our ways, for better and worse, and this is both liberating and a curse. We sometimes spend our whole lives dealing with the demons we have made through patterns we have set as children. But we should also look for the good things we have built into our lives.

While waiting for dinner, we sit by the dock and listen to Nacho talk about this community. Nacho’s grandfather was from Anachucuna. At some point people moved to Armila, but it has always been considered more hostile country. Whirlpools, and sometimes the ocean is so strong you can’t even reach the shore. In certain seasons the community gets a bit isolated.

The Colombians who remained from the banana plantations planted coconuts. The locals fought them and they bought over the land from the company. They used to have ranches with cows but now it is forbidden because it would damage the land.

There is zero tourism in Anachucuna. Nacho only joined us late because he was away at a meeting to discuss the kind of tourism they want to have here. An alternative way of doing tourism, with an emphasis on maintaining nature in its natural state. Carti, seven hours away by boat, has the capacity for 60 people but in the high season there are 500 people. People erode the landscape. The sahilas should represent the community, but they aren’t always interested in tourism. It’s a double-edged sword.

A road is being opened that will be an hour from Anachucuna by boat. So the community wants to be ready for the flow of people that will surely come. The road is something needed. 40% of people in Guna Yala live in Panama City, and it is difficult to travel. The road makes it easier to visit and also to bring produce and goods. It is a door, but unwanted things could also enter. The question of the road has been under discussion for ten years.

‘Tourists are the worst race in the world.’ A nice thought from Luz. We do become a different people as tourists. Heedless of impact, devolved to baser instincts. Hungry to take as much as possible.

This feeds into a discussion I have with Luis after dinner while waiting for the Anachucuna bar to open. In this community, people are allowed to drink from 8-11pm every day, but the only beer available is Atlas, a watered down ‘light’ beer. Thankfully Armila’s beer of choice is MF – the ‘finest American style beer.’ The best beer around here though is probably Aguilar and then Balboa, both Colombian beers.

I was remarking to Luis how I feel that I will never be comfortable as a tourist anymore, even though I will definitely continue to go on ‘holidays.’ Because the depth of experience on this trip has been unparalleled. Luis shares about his experience traveling as a musician, with nothing but his music and the clothes on his back and how people offer him more than just money; they take him into their houses, feed him, invite him in not as a stranger, but as a guest. The tourist is always a stranger, peering into the threshold, insinuating themselves into the picture. The traveler steps over the threshold, is made welcome. Shares something of their own, and is given something in return. The traveler gives.

Scenes from Anachuchuna

But before we head to the bar, Luis appears in the doorway of Baudeliano’s house, looking serious. He beckons to me. I follow him upstairs. Luz is there, looking distressed in the dim light. They tell me that the community has fined me $100 USD for flying my drone without permission. I’m angry, of course, because I had asked and they gave me the green light. But apparently, even the beach needs permission, it wasn’t just about a no-fly zone in the village, it was about asking and receiving the permission of the sahilas. A couple of fishermen who were fishing next to the island saw the drone and reported it. In Singlish, this is summed up as kena sabo (deliberately sabotaged). But I can understand why this happened. It is about protecting the community with a series of rules that seem strict and even draconian. I am not here as a tourist, not wanting to exploit the community. The images are not for commercial use. But it is not about all that. It’s a simple order of things. I, and the group, did not respect that order and so we have been fined. Luz and Luis offer to split the amount with me, which is a relief, because I don’t have that kind of cash buffer. It is a bitter, unfair pill to swallow but I see it this way – how many people have actually been fined by the sahila of a Guna community? I should be grateful they didn’t toss me into a pit of fire ants!

Rough music spills from a large speaker in the bar. According to Maria, ‘bootsandcatsand’ is the best way to replicate the sound of a club beat. It does work, though it feels muffled by distance, or a closed door.

I am trying to articulate why I am feeling and reacting far less emotionally these days. I do write emotionally, but it’s almost as if my body cannot feel extremes of emotion. I am an even keel, unmoved by currents, flippant even in a storm. When asked how long I’ve felt this way, I responded that it’s been a couple of years, at least. And then it hits me. That’s how long I’ve been at my PhD. Somehow, the constant need to think, reflect, process and write about all that over and over has kept me in some kind of narrow emotional channel. Even here, I’ve developed a structure and rhythm to the days. The journal is my way of reflecting on the entirety of the experience while the creative work is a more focused commentary through image and poetry. But even here, I have not given myself permission to play. Everything is ordered, rigorous. I wonder if this is just a PhD thing, or is this my new way of living?